Wine has always been more than a drink. It’s been divine nectar, a symbol of excess, a painter’s muse, and—if you’ve ever had one glass too many—the reason you thought karaoke was a good idea.

From Egyptian tombs to Van Gogh’s vineyards, artists have been pouring wine into their work for over 5,000 years. Sometimes it’s sacred, sometimes scandalous, but always symbolic. Let’s uncork this history together.

Antiquity: Wine Fit for Pharaohs and Philosophers

The Egyptians painted wine in tombs, not as decoration but as a VIP pass for the afterlife. Jars of wine were placed with pharaohs to ensure they stayed hydrated in eternity—because even in the afterlife, no one wants to run dry. These depictions, dating from around 3000 BCE, show the entire process of viticulture: harvesting, pressing, storing. Wine was reserved for the privileged and the divine, standing in stark contrast to beer, the everyday drink of the masses.

As winemaking spread through the Mediterranean, its artistic presence blossomed. The Greeks gave us vase paintings of symposiums—philosophical drinking parties where the line between profound wisdom and drunken rambling was probably very thin. Wine wasn’t just a beverage; it was central to social, intellectual, and spiritual life.

The Romans, ever keen on spectacle, adopted Bacchus from the Greeks’ Dionysus. He became the ultimate party god, flanked by satyrs and maenads in a never-ending conga line of intoxication and theatre. The vine-wreathed figure with thyrsus in hand became an enduring artistic motif, symbolising ecstasy, fertility, and that all-important escape from daily worries.

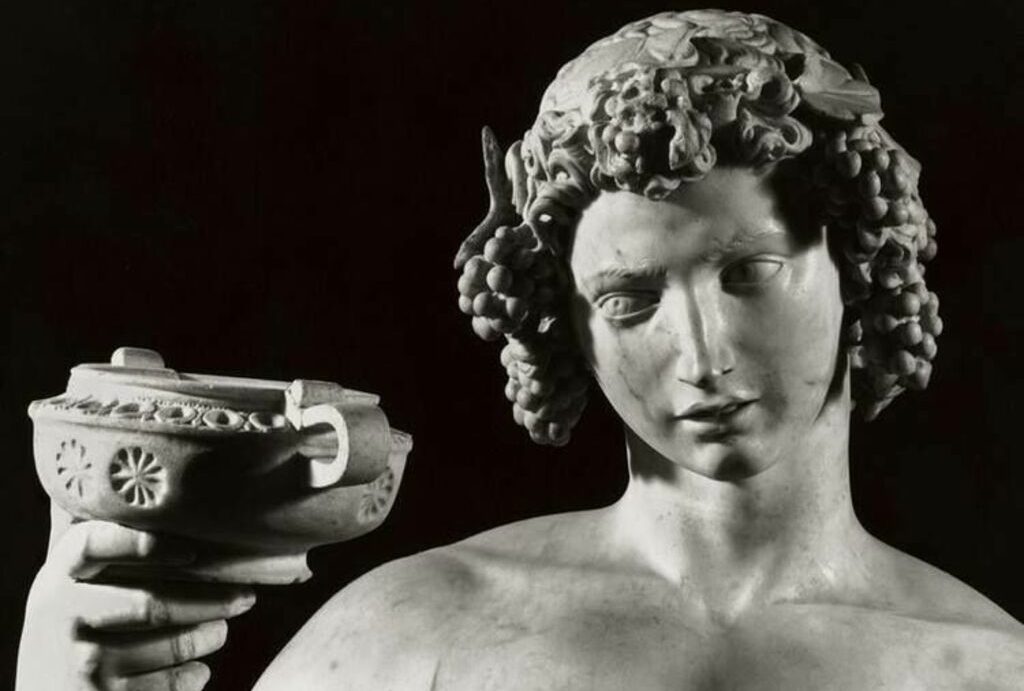

Case Study: Michelangelo’s Bacchus (1497)

Michelangelo’s marble Bacchus shook things up. Unlike the heroic, godlike depictions of antiquity, his Bacchus sways unsteadily, his gaze glazed as though regretting his fourth glass. A satyr behind him cheekily nibbles grapes, a reminder that wine makes fools of gods and mortals alike. It was too human, too vulnerable for its patron—who rejected it. Yet this humanity was exactly what made it revolutionary.

Michelangelo’s marble Bacchus shook things up. Unlike the heroic, godlike depictions of antiquity, his Bacchus sways unsteadily, his gaze glazed as though regretting his fourth glass. A satyr behind him cheekily nibbles grapes, a reminder that wine makes fools of gods and mortals alike. It was too human, too vulnerable for its patron—who rejected it. Yet this humanity was exactly what made it revolutionary.

Sacred Sips: Christianity and Wine

When Christianity arrived, wine swapped wild festivals for holy rituals. Think less toga party, more The Last Supper. At Cana, Christ’s first miracle was turning water into wine, a transformation that symbolised divine abundance and blessing. Later, during the Last Supper, wine became even more profound: Christ declared it his blood, creating the Eucharist, a central sacrament still practised today.

Artists took note. Paintings and frescoes of the Last Supper abound, from Leonardo da Vinci’s iconic mural to countless altarpieces where chalices glisten with deep red wine. The symbolism was clear: this was no longer Bacchus’s potion of liberation, but Christ’s gift of salvation.

Case Study: Veronese’s Wedding at Cana (1563)

Veronese’s Wedding at Cana is a banquet like no other. At nearly 10 metres wide, it’s a riot of colour, architecture, and fashion. Biblical figures mingle with European royals and Ottoman sultans. The miracle unfolds amid dazzling pigments and theatrical grandeur. The wine here isn’t just a drink—it’s a bridge between divine intervention and worldly celebration, an eternal party where the sacred and secular clink glasses.

Baroque and Beyond: Realism, Revelry, and a Touch of Rot

By the Baroque era, art was less about divine abstraction and more about gritty realism. Cue Caravaggio, who painted a Bacchus that looks like the slightly sweaty friend offering you “just one more glass.” Beside him, luscious fruit sits on the table—until you notice the worm-eaten apple. A reminder that life, like wine, eventually turns.

Velázquez’s The Triumph of Bacchus (1628–1629)

Velázquez went further. His Triumph of Bacchus shows the god crowning a peasant, surrounded not by gods but by rugged Spanish drinkers. It was a statement: wine’s gift wasn’t just for emperors, it was for everyone. It consoled the working man as much as it liberated the elite. In Velázquez’s hands, Bacchus became the people’s god.

Velázquez went further. His Triumph of Bacchus shows the god crowning a peasant, surrounded not by gods but by rugged Spanish drinkers. It was a statement: wine’s gift wasn’t just for emperors, it was for everyone. It consoled the working man as much as it liberated the elite. In Velázquez’s hands, Bacchus became the people’s god.

Dutch Golden Age: Wine as Lifestyle Accessory (and Moral Trap)

The 17th-century Dutch had a different relationship with wine. Still lifes featuring wine, oysters, and lemons were like status updates, showing wealth and refinement. The delicate glassware itself became a symbol of sophistication. Collectors proudly displayed these paintings as evidence of their cultured taste.

But alongside celebration came cautionary tales. Jan Steen’s rowdy household scenes warn of drunken folly, where passed-out parents and mischievous children remind viewers that too much merriment leads to chaos.

Case Study: Vermeer’s The Glass of Wine (c.1660)

Vermeer’s The Glass of Wine captures the moment between temptation and restraint. A man pours wine for a lady while, in the background, a stained-glass figure of Temperance silently frowns. It’s an exquisite metaphor: wine as pleasure, but also as moral crossroads.

Vermeer’s The Glass of Wine captures the moment between temptation and restraint. A man pours wine for a lady while, in the background, a stained-glass figure of Temperance silently frowns. It’s an exquisite metaphor: wine as pleasure, but also as moral crossroads.

Modern and Contemporary: From Canvas to Label

By the 19th century, wine had left the altar and tavern for Impressionist picnics and Post-Impressionist vineyards. Renoir painted convivial joy in Luncheon of the Boating Party—friends, laughter, and clinking glasses. Van Gogh, meanwhile, painted The Red Vineyard with fiery strokes, turning the act of harvesting into a mirror of his own turbulent soul.

Fast forward, and wine becomes art itself. Since 1945, Château Mouton Rothschild has invited artists from Dali to Warhol to design its labels, turning bottles into collector’s items. Wineries today embrace the gallery concept—HALL Wines in Napa, Sculpterra in Paso Robles, and Waddesdon Manor in the UK merge sculpture parks with tasting rooms. Wine isn’t just drunk, it’s experienced as an artistic journey.

The Enduring Romance

From tomb walls to tasting rooms, wine in art reflects humanity’s deepest dualities: sacred and profane, joyful and melancholic, fleeting and eternal. Artists used it to celebrate, to warn, to symbolise, and to seduce. The imagery has shifted, but the message remains: wine, like art, tells us who we are.

So next time you lift a glass, remember: you’re part of a story that stretches back millennia, from pharaohs to Van Gogh, from Bacchus to Bordeaux. And that’s something worth toasting.

Cheers to that. 🍷